Does a Balanced NFL Rushing Attack Lead to Better Outcomes?

Specialization or Generalization?

Tuesday could go down as one of the more monumental days in the history of the football analytics community. Seemingly everyone I know who posts public work found themselves immersed in yet another new artificial intelligence model.

SumerSports released a beta version of SumerBrain, an AI model that responds to NFL-related questions using the company’s proprietary tracking data. But, instead of having football experts chart literally everything manually, a deep learning model builds off raw information to come up with new insights. The model is validated by humans, but coupling these results with a language-learning model means users can ask SumerBrain any question it would have accessible data about, and the AI can provide a response. But, as with any AI tool, there can be hiccups, so a watchful eye is still necessary.

While this tool is publicly available, some data that may have previously been behind some company’s paywall is now in the open. For instance, there are many ways an offensive line can block on a run play. There’s zone blocking where every lineman is assigned an area instead of a defender, dealing with anyone in their zone. There’s man blocking that’s exactly what it sounds like: an offensive lineman is trying to move a defender out of the way. Finally, there’s gap blocking which is in-between the other two schemes, where linemen are blocking away from the gap where the runner is going. There are other types of schemes for specific situations, but these are the main three worth analyzing.

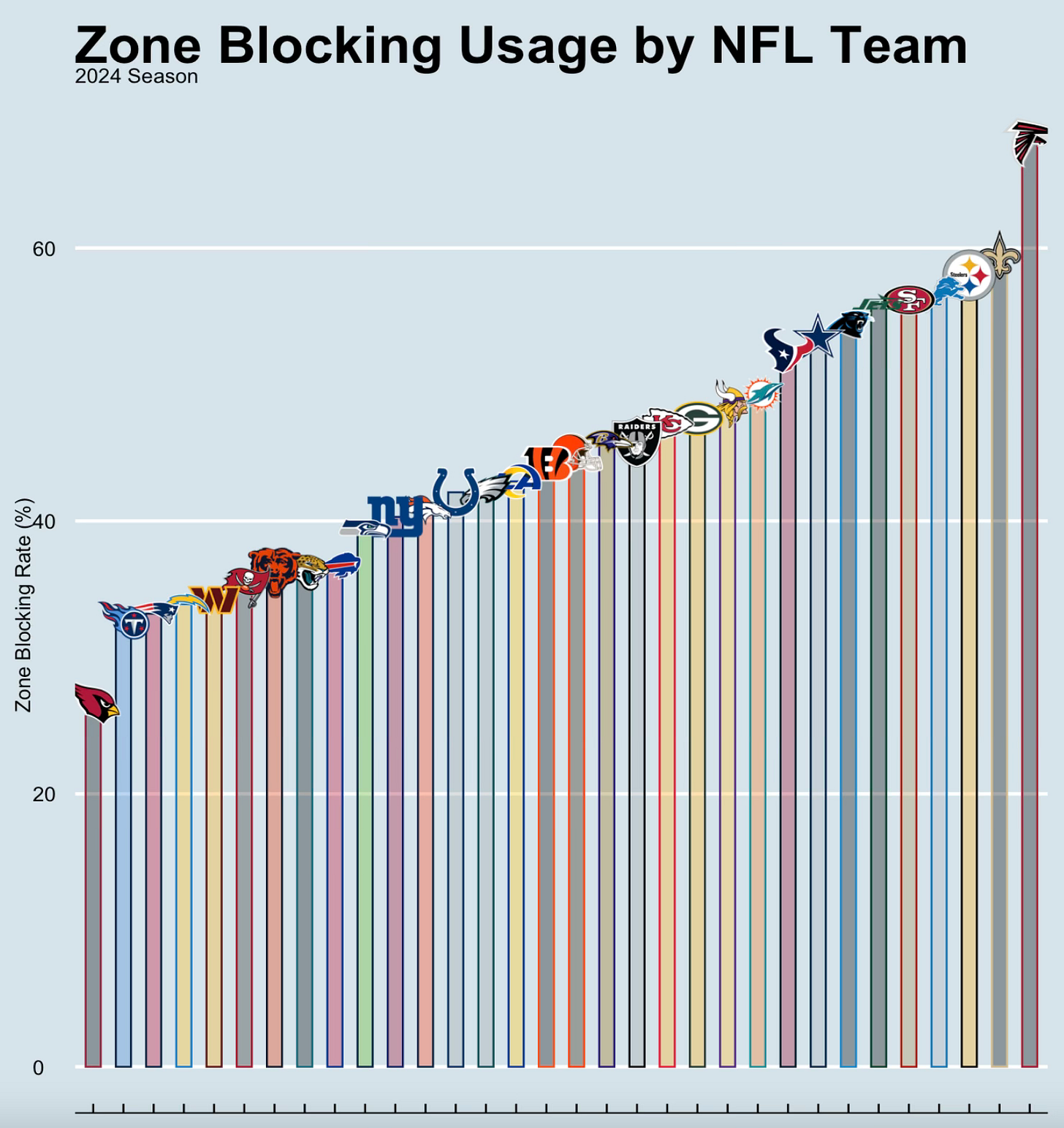

In many other contexts, I have explored how valuable unpredictability is to a team’s success. Thanks to blocking data from SumerSports, here is where we can explore if teams that diversify their schemes are more successful than those rely heavily on one approach. First, it’s worth noting more teams select zone blocking than any other, at least during the 2024 season:

To measure unpredictability, I will return to the same concept I referenced before. Shannon entropy is a way to measure the uncertainty of a variable, as part of information theory. As new information about a variable is transmitted, probabilities are communicated as well based upon how surprising or rare that information is. In other words, variables with a 50-50 chance of some binary outcome occuring are considered more unpredictable, and these results have a higher entropy. However, when we can safely gauge what will happen with an outcome, we come up with a lower entropy.

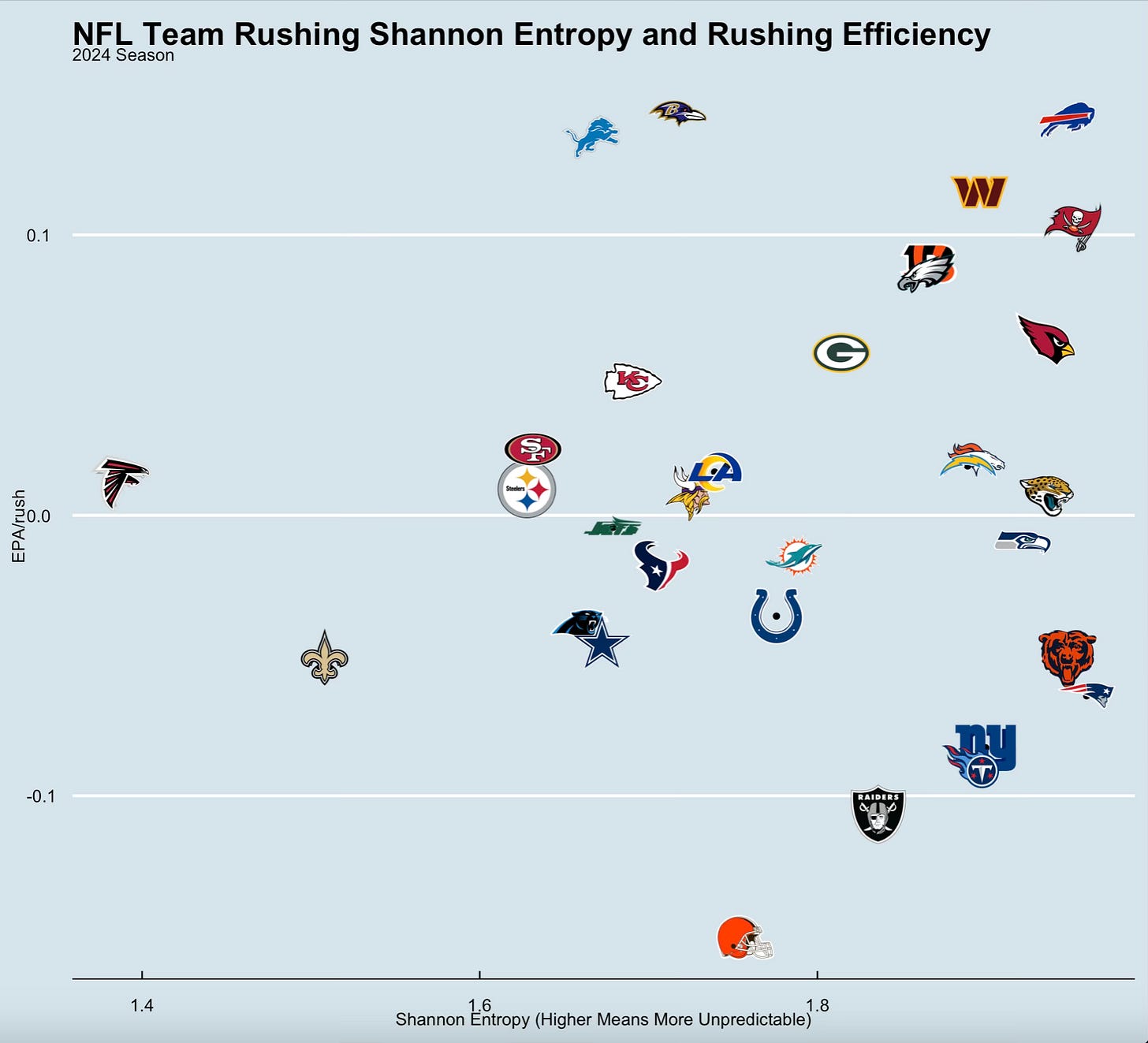

What we want to know is if entropy has any effect on rushing efficiency. For this exercise, let’s use expected points added per rush (EPA/rush). Plotting these two metrics, here’s the distribution:

It’s hard to see a clear correlation between entropy and EPA/rush. While the Atlanta Falcons are almost always resorting to zone runs, other teams try to be more unpredictable, but with different levels of success. The New England Patriots are virtually as unpredictable as the Buffalo Bills, but one is clearly more effective than the other. Just to be sure, let’s include a LOESS regression to try and capture the behavior of these points:

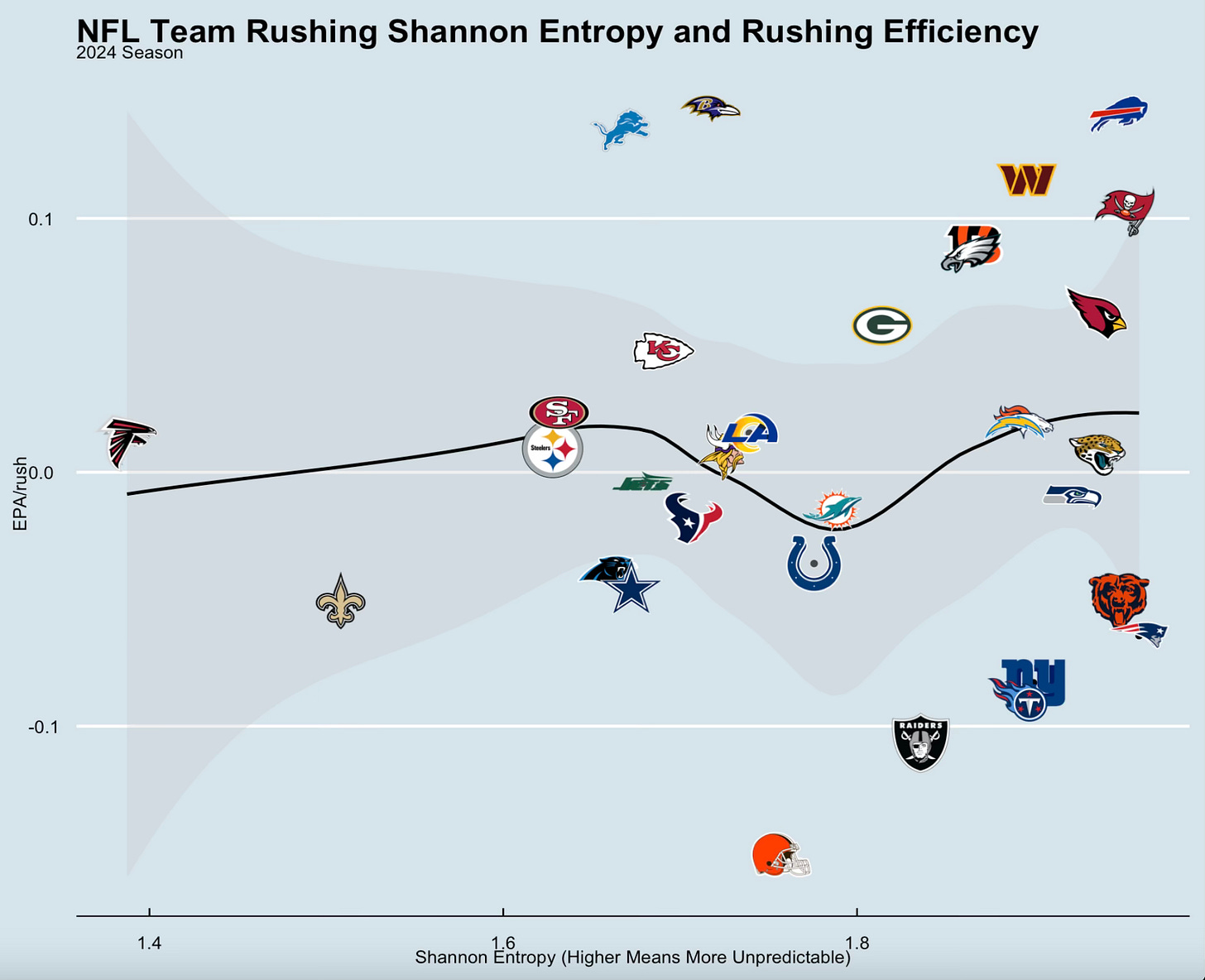

There may be some usefulness once you get past the valley around a Shannon entropy of 1.8, but it’s hard to see if this information is actionable. In other words, if there is value in being unpredictable, the rushing attack must first be effective, then there may be a slight advantage, but not much of one.

This study may not have illuminated anything, but it would not have even been possible had these data not been available. What any AI tool should do is provoke additional questions and possibilities. Not every exploration will yield something, but eventually, the follow-ups will.